Discovering Evil: The Proximity of The Propagandist

Bouwman’s film is no exception. Using a wide selection of archival footage, such as propaganda works, interviews, sound recordings and even home movies, The Propagandist uncovers the life story of Jan Teunissen, a figure long obscured by history, who was the most powerful figure in Dutch cinema during the nazi occupation of Europe and the Holocaust. He produced – and was in charge of – propaganda works imbued with nazi ideology which is why he is often referred to as the “Dutch Leni Riefenstahl“. The 2024 documentary Riefenstahl, directed by Andres Veiel bears resemblance to The Propagandist in several ways. Both films represent a contemporary documentary approach by using archival materials in a peculiar way and by placing perpetrators in the center of attention instead of victims. Consequently, the works are highly reflective. They seek to differentiate the viewer from the perpetrator’s point of view and to ensure that the propaganda footage and recordings are interpreted appropriately.

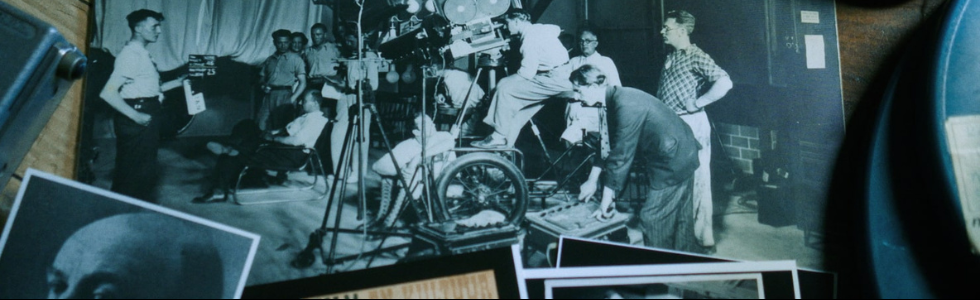

However, the greatest difference lies in how they utilize film heritage in relation of reflexivity. Both films are stylized in their own way. Veiel, whenever he shows analogue copies of Riefenstahl or her propagandistic works, shows the actual physical film reels and often creates poetic sequences that display the individual frames in motion. In this way, “he breaks down the reality“ of the propaganda films, interviews and images of Riefenstahl. He intends to make visible the deceitful nature of film and the character from the very beginning. By contrast, in The Propagandist Bouwman reinforces the illusion of reality and the feeling of familiarity. The film utilizes the archival footage in an unusual way. In several interviews Bouwman talks about the digitization and restoration process of the materials used. The digital restoration results in life-like, crystal clear images, which immerses the viewer deeply. The only direct visualization of archival material is provided by a few close-up shots of a sound recorder, which relates to the basis of the film, a 7 hour and 45 minutes recording of an interview made by Rolf Schuursma with Teunissen in the 1960s. Other than that in some cases it is almost undetectable whether the actual footage is a restored analogue clip or just a scene recorded for the movie. To counter the propagandistic effect of Teunissen’s voiceover and the realism of the restored footage, Bouwman inserts reactions of historians, and this helps the viewer to orientate. Nonetheless, the realism factor remains significant.

Veiel in Riefenstahl often manipulates the images, distorts them, or zooms in on faces, and even in some scenes we can see a close-up of Riefenstahl tinted in red. These visual manipulations are followed by intense sound effects and music, thereby reinforcing the desired outcome. Veiel wants to prove Riefenstahl’s culpability. On a narratological level from the very beginning of the film this intention is realized. He uses – and more importantly, oversaturates – the archival material for this very reason. Often we can hear his voice as a narrator, which is followed by a footage to prove his statments. Bouwman has stated in an interview that he „does not like to invent images” and to alter them in this way, because avoiding these solutions „adds to the [film’s] authenticity”. So these sharp and crisp images are stylizing the film, but it has an effect of a type of realism. Other than Teunissen and other filmmakers, historians we cannot hear the maker of this film as a narrator. In some scenes there are short inserts to connect not so complete footages, but an outside perspective other than Teunissen is completly derived in the scenes with archival material. The Propagandist’s narrative tries to postpone the final moral judgement as much as possible, even if the viewer can sense contradictions while listening to the historians reactions. Therefore the film feels like a natural – and in this way, realistic – discovery of a person who did evil things, rather than a demonizing representation of one.

On the other hand, this degree of realistic stylization creates a sense of familiarity, making the film’s subject matter feel far less like a distant remnant of the past. The Propagandist embodies the tendency that we often forget what happened in the past. It reminds us that the absurdities of history are not as alien in our time as we might think.

References:

Koch, JJI: The ethics of representing perpetrators in documentaries on genocide. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 27 (5), 928–946.

Nichols, Bill: Introduction To Documentary. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Rapold, Nicholas: Crimes of Opportunity: Luuk Bouwman on His Portrait of a Nazi Official, ‘The Propagandist’. https://www.documentary.org/online-feature/crimes-opportunity-luuk-bouwman-his-portrait-nazi-official-propagandist

Szalontai Marcell, Kovács Nikolett: 'We talk about gray tones a lot but there is also black in actions that people do'| The Propagandist. https://youtu.be/cHa5elAwG8E?si=0tTFYHbXbDaJ_OzI

The article was created as part of the UniVerzió program, in collaboration between the Verzió Film Festival and the Department of Film Studies at Eötvös Loránd University. Instructor: Beja Margitházi.