Breaking the Taboos of Trauma (Bigger than Trauma)

The long process of their traumatization is propelled by never-ending anxiety and fear, which (although now without external reasons) demand a constant state of vigilance and induce immense amounts of stress that consumes much of their emotional resources and physical health. We as viewers are presented with their personal recollections of their current lives and its main persistent problems related to fear, but beyond that lay the constant feeling of shame they experience daily as members of their respective communities due to merely having survived the atrocities committed to them by both Serbian and Croatian militiamen. This ludicrously gave them the air of having been complicit with their perpetrators who brought destruction to whole villages in the Balkan wars. This (although obviously irrational and unjustified) shame is a hugely determinant aspect of the identities of each of the main characters, and has had further dire consequences in their lives before. The general isolation and loneliness they needed to endure due to these “shameful” secrets they have been keeping for decades and consequentially hiding their own pain made them feel completely alone until the restorative therapy sessions followed meticulously and sensitively by the filmmakers. The shame induced their lack of self-worth, which has rendered their sense of femininity and strength as women oftentimes completely diminished or broken.

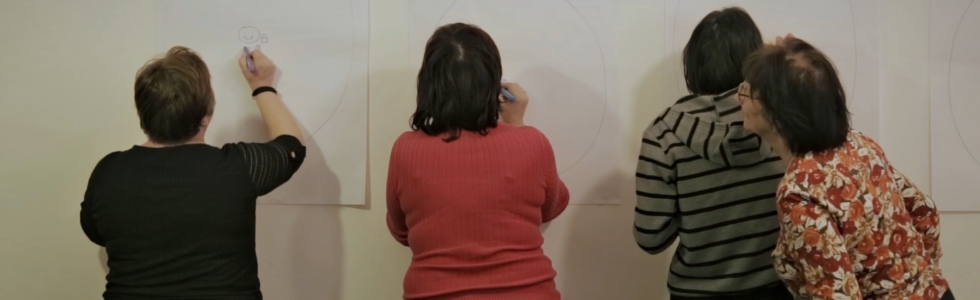

The burdens these women have had to carry coerced them into a sense of helplessness in controlling their own stories, and this is the very core of why the therapeutic process they go through together (besides having shared similar traumatic and trauma-induced experiences) seems to achieve elemental and lasting success in transforming their lives. During the multidisciplinary therapy sessions in the program of Bigger than Trauma, the survivors of wartime rape are provided a safe and attentive environment to process their traumas, pains and grieves, while also learning multiple practical core mechanisms to manage their emotional health more effectively, and having attention paid to themselves defined by as much more than their shared traumas.

From more sociological and public policy perspectives, the film of Vedrana Pribačić and Mirta Puhlovski also implies that there lies a systemic problem in form of the unspoken of and unprocessed traumas, shame and taboo of thousands of wartime rape survivors in the ex-Yugoslavian countries, all of which display extremely low levels of mental health access in rural areas (as is the problem for many other countries in the Central-Eastern-European region). This could be one of the underlying factors behind the overall mental health attitudes of the represented cohort consisting of middle-aged women who were all brought up in closed, rural communities run by traditional values. The protagonists share a kind of internalized stigmatization and shame that is reminiscent of those generally participating in therapy for any other reasons – however, being surrounded by a much deeper and magnified version pain.

Isolation in some form is one of the main aspects of how they deal with their rape in hiding it to some extent from their own environment to suppress shame. This sentiment of isolation is present in every field of their lives. They are middle-aged women from the Croatian countryside without meaningful and honest connections to their respective communities, or even families. Furthermore, they are all isolated by internalized shame from these communities by the stigma of continuous rape and torture, as they seem often to be accused of being complicit merely by survival. The aforementioned two different forms of isolation culminate in a total disconnectedness from real, meaningful social and emotional relationships due to their lack of trust, general anxiety and lack of self-worth. Still, through the therapeutic process and constant positive reinforcement of their progress in the healing process, the women who undertook this journey together seem to evolve as persons together, providing support and love to each other in their lives following therapy. They do not have many friends at the beginning of their therapeutic journey, however, multiple true friendships have been forged through their shared healing experience.

Besides the taboos of rape being broken in a circle of trust and collective support in the therapy sessions presented in the film, it also breaks an additional taboo: the taboo of therapy in general. Participating in any kind of therapy entails potentially being subjected to flawed yet persistent stereotypes by one’s own environment. This effect is enhanced especially in smaller, rural and more religious communities with more traditional views of how strong women or matrons should behave. The women participating in the since shutdown program display another form of courage in owning up to participating in therapy to their environment – and the public at large. In addition to this, the special multifaceted therapeutic approach is exerted on them in a special setting: in form of a group therapy with peers. After a while, the participants in this group process become comfortable enough to cooperatively break the taboo of always needing to seem strong and composed as women in front of your peers by opening up to each other and allowing themselves to be and seem as vulnerable as humanly possible. Their story inspires us, the viewers through allowing themselves to seem so vulnerable, and trusting the filmmakers to immerse us into these therapy sessions through carefully choreographed yet not overly intrusive compositions – in turn, evoking our empathy and deepest sympathy to the women who dared to share their deepest secrets with us.

Sára Kende

ELTE BTK Film Studies MA