Oksana Sarkisova (OS): Congratulations on completing this powerful and extremely relevant film. You studied science, have a degree in molecular biology and finished a business school. You are also known as a popular blogger. How have you become a documentary filmmaker and have your earlier studies helped you in some way on that path?

Hao Wu (HW): I have always been interested in storytelling from a young age. But in China, if you do well academically, you’ll feel the pressure to pursue science, technology and other fields that more often lead to a stable career. That’s what I did – science first, and then management. But I always attempted something creative on the side, as a hobby. I started making films while I was a tech executive. Eventually I decided to quit my management career to focus full time on filmmaking, because the creative process itself is extremely satisfying. My past career experiences have a great impact on how I approach filmmaking. The scientist in me rejects any easy categorization, any easy answer to complex social and human dilemmas. The business training I had has helped me in various producing tasks around the making of a film. I always lead produce the films I make.

Photo: Hao Wu

OS: How you worked on the film with your co-directors?

HW: In early February I started researching a film about the coronavirus outbreak. I was in New York then and I reached out to filmmakers who had begun filming on the ground in Wuhan. After speaking to over a dozen, I found my two co-directors whose footage, with unprecedented access to the frontline, shook me. Soon we began collaborating over China’s Great Firewall, sharing daily rushes over the cloud and discussing which characters to follow and what new story angles to explore. By late March, China had tightened its control over any COVID narrative so much that both of my co-directors stopped collaborating with me. They worried that I might take their footage and make a film which would get them in trouble with the government. Since I had already downloaded their footage, I went ahead with editing. Once I edited out an entire rough cut, I showed it to them, to demonstrate my creative intention. Only then did they grant me legal permission to use their footage in 76 Days.

OS: Why has your colleague preferred to stay anonymous in the credits?

HW: "Anonymous" is a Chinese reporter who is also a first time filmmaker. Due to the sensitivity around any COVID-19 narrative in China, he would like to remain anonymous to avoid attracting attention.

OS: Was it easy to convince the hospital to let the film crew and how was the agreement about what was allowed to film?

HW: My two co-directors are reporters who were sent to cover the outbreak in Wuhan. During the lockdown, the Chinese government restricted access to hospitals to only patients, medical professionals and reporters. A few of the hardest-hit hospitals only allowed reporters and filming crews thoroughly vetted by the authorities. But that strict control was not applied uniformly to all hospitals or throughout the entire lockdown period. Early in the lockdown when the situation was dire and chaotic and there was a severe shortage of medical supplies, many hospitals actually welcomed media exposure to help them look for help. Some of the medical teams sent from elsewhere in China to support Wuhan were also open to being filmed, partly due to their desire to have their own images documented in this historical moment.

OS: Wuhan lockdown lasted 76 days as your film reminds us. How long was the shooting going?

HW: Production started in Wuhan in February 2020, soon after the lockdown on Wuhan began, at four different hospitals. It continued through the gradual return of order and ended after the lockdown was officially lifted on April 8.

OS: How have you made decisions about the film’s structure?

HW: In early April, I saw a video on Chinese social media about the national mourning day. I cried while watching. I immediately knew that that should be the ending of 76 Days – not only to give audiences an emotional release after watching such horrendously tragic stories, but also to pay respect to all those who had sacrificed. That decision helped build a “container” around the film – from the beginning of the lockdown to the end. Within that overall structure, I followed my emotional instinct and picked out the strongest, the most moving scenes out of the footage shot by my co-directors. Since inside the hospitals it was chaotic most of the time, my co-directors had a difficult time determining who might be the “main” characters to follow. So they followed many different characters, and I ended up assembling a group portrayal of the medical workers and patients, with different characters appearing at different frequencies.

Another decision I made was not to use any news clips or social media videos to provide any factual details about the Wuhan outbreak and subsequent lockdown. The more I edited, the more I realized that the most valuable aspect of the footage was how emotional raw it was. So I wanted to strip away any specific geographical, social and political context, in order to focus the film on the emotional experience living through a catastrophe, which is common to people everywhere.

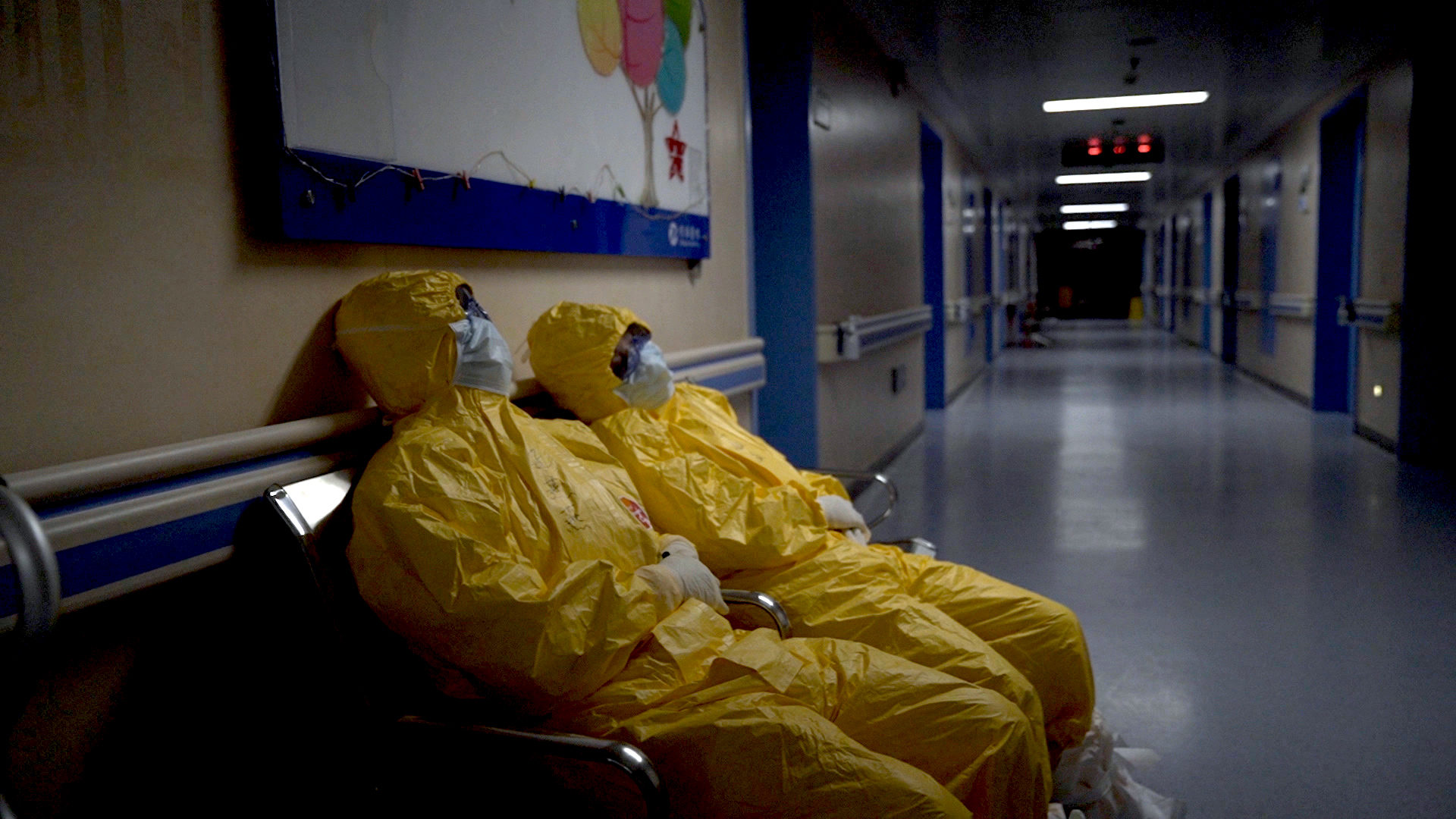

Photo: 76 Days

OS: Are there scenes that you could not or were not allowed to include to the film?

HW: There are many scenes we cut out, for creative reasons. We had filmed characters outside of the hospitals. We had also interviewed others. But in the end, I took them all out because they would distract from the tense scenes inside the hospitals.

OS: You grew up in China and have lived in the US for a long time. What are the main differences in the way the two countries handle the pandemic?

HW: It’s hard to generalize for any particular country, because a particular leadership would behave differently in crises like the one we are living through right now. I’m pretty certain if COVID-19 had happened during the Obama presidency, we would have had a different response here in the US with a drastically different outcome. Still, some differences between China and the US would have existed even in that scenario. The authoritarian political system in China would likely remain more efficient at mobilizing resources and implementing harsh measures to control the pandemic. The population – similar to many other Asian countries’ – would also likely be more willing to follow directives from the government. Here in the US, with the society increasingly polarized over a deep ideological divide, it would require a strong leadership at the very top and meaningful bipartisan collaboration – hard to foresee now with any presidency – to get the entire society behind effective yet painful public heath measures.

OS: What was the most important lesson you learned in the process of working on the film?

HW: It’s easy to see the human follies that often make a pandemic worse than it could have been. It’s easy to lose hope at human beings’ potential for collaborative response to combat a natural disaster. But making 76 Days reminded me that even in the scariest and most desperate days of the COVID-19 outbreak, there’s ample evidence of human kindness, of our desire and willingness to connect, to comfort, to help. So there’s still hope.

Interview: Oksana Sarkisova

The interview was published in Hungarian in Magyar Narancs on 5 November, 2020.