The news story, about a Hungarian tribe in the Congo called the “Madjari”, lasted a day and a half until a journalist from index.hu tried to reach the institute mentioned in the article, and thereby uncovered the person behind the media hack, journalist András Dezső.

What does the Madjari tribe’s 36 hours of fame tell us in 2019? Picking and choosing relevant or interesting information from the mass of news, data and general output circulating and targeting us has become part of our daily routine. Without this personal filter, we wouldn’t be able to absorb the vast amount of information thrown at us on a daily basis. However, when scanning social media, we often activate another filter as well; we pay attention to where certain news items come from, or which website/media company published it. It is always reassuring to read something from a familiar site—one we consider legitimate—and hence obtain knowledge from a world we think of as authentic. Hacked questions this very practice. It shows us that constructing a new reality that we would accept, without challenge, takes only a few minutes. Thus, the film calls our attention to the functioning and anomalies of the media. As journalist Zoltán Szabó mentions in the film, the media often uses news they receive in a “ready-made” form, without interpretation or alterations. This is not only problematic in a case like the Madjari news item, but it is also remarkable that a press release can be published on a website located in the UK, where in 2007, one could upload content without regulation.

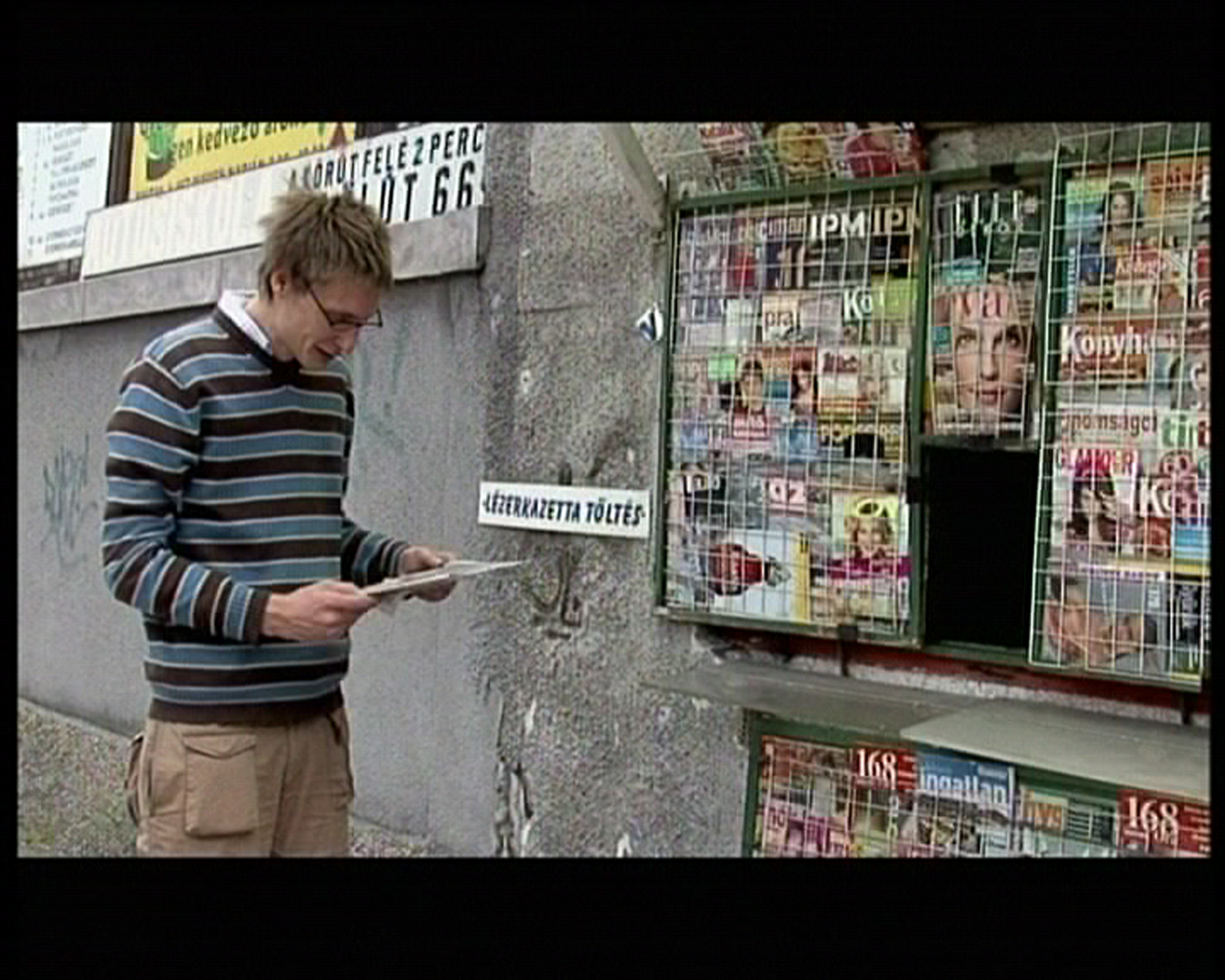

In terms of media consumption, 2007 almost puts the film in a historical context. Today, media content is produced and consumed much faster, and as a result of technological developments, we can find anyone or anything on the web in a few minutes, even while walking down the street. While the speed of accessing information accelerates, it takes less and less time to produce content. Moreover, as the amount of information grows, so does the number of accessible realities, of which weonly see our filtered version.

It seems that current regulations are no match for the sheer amount of information produced, especially on the web (this is why, for instance, Facebook has created its own censorship system, with its employees reading and filtering out posts with harmful or upsetting content).

Photo: Hacked

Hacked initially seemed like an innocent practical joke; Dezső even mentions that he has an idea that has nothing to do with politics and scandal, which he could turn into a hoax. However, as more and more journalists contact him—or rather his alter ego, anthropologist Gábor Varga—we become increasingly uncomfortable with his tangled web of lies, not only for the sake of lying itself, but because of the unchallenged attention this ridiculous story receives so quickly. One has to wonder, how fast a message in made bad faith, inciting hatred or openly expressing propaganda could spread? As Dezső promises to appear on television and show (non-existent) video footage of the tribe, we become progressively excited, even if we can guess how it will all end. Thus, the practical joke that started in a living room becomes more and more thrilling, and the “hoax” begins to point to things beyond itself; this is just an innocent piece of fake news, but how is it different from fake news on Facebook, donation requests for fictitious causes, or unethical and manipulative political messages? They work on the same pretty-packaging principle: the deep-seated gut feeling that whatever is on TV, in the papers or on the Internet must be true. Hacked challenges and questions this basic assumption, and potentially encourages us to question the exclusive truth of the written word and the media image.

Naturally, this is also valid for film: the truth of its content should be questioned. We could also ask if this is really a documentary; how much of the story was constructed in advance—and if it was, does it cease to be a documentary? Ethical issues also arise, not foremost among them, lies stated in a press release are later explained by a second press release, just as re-dubbed recordings can be found on the Internet, thus entirely changing the content of the original recordings. This could open a whole new topic about whether the end justifies the means.

In spite of its formal and potentially technical weaknesses, Hacked is quite an important film, because even with a very simple argument, it helps us question and rewrite how we select, take in and interpret the mass of information we are faced with every day, and it points at the necessity of questioning the things we would otherwise take for granted.

Hanna Eichner

This article was published in a special edition by Verzió and Utca&Karrier in October 2019.